Can you use WHATWG Streams for reactive programming? It seems so. But is it a good idea?

Reactive Programming?

The Reactive Programming (RP) paradigm is not new and has enjoyed popularity in many different genres of programming. For example Android folks, especially since the introduction of Kotlin, have seen a rise in popularity around RP. I have also noticed some game engines experimenting with RP. On the web there have been a number of attempts to enable reactive programming. RxJS, MostJS and CycleJS come to mind. More recently, Svelte 3 implemented a slightly different take on reactive programming.

Reactive programming in general as well as these specific implementations are well covered on the web, so I won’t write yet another introduction to RP. But I want to make sure we are on the same page: According to Wikipedia, “reactive programming is a declarative programming paradigm concerned with data streams and the propagation of change.” (Emphasis mine.)

Most of the RP libraries I looked at use a model centered around “observables”. An observable is a type on which you can register “observers”, as defined in the observer pattern in the GoF book. For the time being, you can think of an observer as a callback in JavaScript land:

myButton.addEventListener("click", myClickHandler);

In this example, myClickHandler would be the observer, while myButton is an observable. Kinda. I hope the differences become clearer throughout the remainder of this blog post.

Note: As I said before, there are many libraries that enable RP on the web. I am going to mostly focus on RxJS because their documentation was my main reference.

RxJS implements an Observable type and also ships many utility functions, for example to turn a button into a proper observable:

import { fromEvent } from "rxjs";

const observable = fromEvent(myButton, "click");

observable.subscribe(event => {

/* ... */

});

Just having a different syntax to subscribe to events is not really that interesting, though. What makes RP really powerful is the ability to encapsulate behaviors or kinds of data processing. RxJS calls these encapsulations “operators”. You can connect multiple observables into a whole graph of data streams using these operators.

An operator takes an observable and returns a new observable, giving the operator a chance to mangle or transform the data. This can be a basic transformation like a map or filter which you might know from Arrays. But the transformation can also be more complex like debouncing high-frequency events with debounce, flattening higher-order observables (an observable of observables) into a first-order observable with concatAll or combining multiple observables into one with combineLatestWith.

Here is a RxJS example using a debounce operator:

import { fromEvent } from "rxjs";

import { debounceTime } from "rxjs/operators";

fromEvent(myButton, "click")

.pipe(debounceTime(100))

.subscribe(event => {

/* ... */

});

When you fully embrace RP, the core of your app ends up being a declaration of a graph through which your data flows.

Streams

WHATWG Streams (or just “streams”) are a relatively new, low-level platform primitive and are prominently used in the Fetch API to model request and response bodies. You could describe them as a special case of asynchronous iterators, tailored to model network traffic (and I/O in general).

Why look at streams in the first place? I always felt like streams and observables are just a rose by another name. Even Wikipedia’s definition of RP mentions “streams of data”. Then why are streams and observables rarely mentioned together? Why is there a separate TC39 proposal for observables when we already have streams? Why is RxJS not built on top of streams? Am I missing something? Yes. Yes, you are, Surma.

Sugar

The quite minimal RxJS example above would look as follows when written with vanilla streams:

const stream = new ReadableStream({

start(controller) {

myButton.addEventListener("click", event => controller.enqueue(event));

}

});

stream.pipeTo(

new WritableStream({

write(event) {

/* ... */

}

})

);

This is much more verbose than the RxJS example. But with some helper functions to act as syntactic sugar, we can achieve not only comparable terseness, but even comparable syntax. I decided to collect these helpers in a little proof-of-concept library that models observables with streams as its underlying type. Not only would this be a fun exercise, but it will allow me to explore the differences between RxJS’ take on observables and mine. It’s called observables-with-streams (or “ows”) and is available on npm.

With this library in place, the above example can be simplified:

import { fromEvent, subscribe } from "observables-with-streams";

const owsObservable = fromEvent(myButton, "click");

owsObservable.pipeTo(

subscribe(event => {

/* ... */

})

);

I also implemented a decent number of operators in ows. The debounce example from above looks like this when using ows:

import { fromEvent, debounce, subscribe } from "observables-with-streams";

fromEvent(myButton, "click")

.pipeThrough(debounce(100))

.pipeTo(

subscribe(event => {

/* ... */

})

);

I used RxJS’ excellent documentation as my reference for all the operators I implemented, as it seemed like a good idea to mirror RxJS’ behaviors and use what has already been tried and tested. If you want to know which operators ows currently provides, take a look at the documentation. At this point also a massive thank you to Tiger Oakes (@not_woods) who wrote a good chunk of the documentation!

Analysis

Are streams a suitable replacement for observables? After all, just because code looks similar doesn’t mean it behaves the same. This required some more thorough investigation.

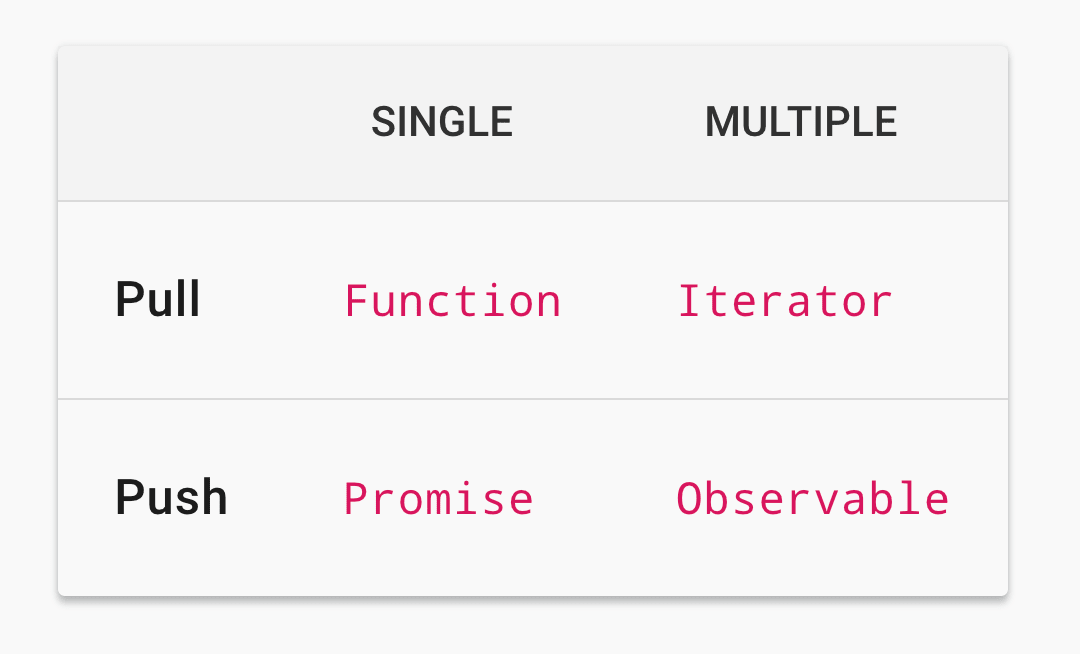

Push vs. pull

When it comes to modelling data sources and data sinks, there’s a common dichotomy of “push” vs. “pull”. In the simplest terms: In the push model, the data source lets sinks know when there is new data to consume. In a pull model, the sinks let the sources know when they are ready to consume more data. The question whether a certain implementation is push or pull does often not have a clear answer, as it is a matter of perspective.

One distinguishing aspect: The pull model is inherently single-consumer. When a sink pulls a value, it now owns it and that value has been removed from the source. Streams specifically implement a pull model, as you pull the next value from a StreamReader:

// Get the stream’s StreamReader.

// There can only ever be one reader at a time.

const reader = someReadableStream.getReader();

// Pull the next value

const nextValue = reader.read();

nextValue.then(({ value, done }) => {

/* ... */

});

The fact that value is wrapped in a promise does not change the pull nature of a stream. You have removed the next value from the stream and you now own it. The fact that the actual value will be delivered asynchronously, doesn’t change that. This design choice makes a lot of sense considering what WHATWG streams were designed around: network traffic. Streams are used in the Fetch API for upload and download payloads, and in these scenarios, data that has been been consumed is gone. As these payloads can be quite large, no system should keep a copy of the data around by default, unless explicitly instructed to do so. If you do run into a situation where you need to accommodate multiple consumers, you can use the tee() method. This will consume the original stream and return two new ones that will output the same data.

import { fromIterable, subscribe } from "observables-with-streams";

const owsObservable = fromIterable([1, 2, 3]);

const [o1, o2] = owsObservable.tee();

o1.pipeTo(subscribe(v => console.log(`Subscriber 1: ${v}`)));

o2.pipeTo(subscribe(v => console.log(`Subscriber 2: ${v}`)));

A beneficial aspects of a pull model is the sinks’ natural ability to “communicate” with a source. Whenever it pulls from the source, it can pass along some auxiliary data, e.g. to signal “back pressure”. The source could then react to this signal by, for example, stopping to generate more data until the sink has worked through the backlog. Streams support backpressure which is important for efficient network communication.

Observables on the other hand implement a push model. You register a callback (or observer) with an observable which will be invoked by the observable. It pushes the value to you. Observables can have multiple subscribers, as opposed to the single-subscriber nature of the pull model.

The fact that observables and streams implement different models does manifest in diverging behavior in some cases. Here’s an example:

import { Observable } from "rxjs";

const rxObservable = new Observable(subscriber => {

setTimeout(() => {

subscriber.next("hello world");

subscriber.complete();

}, 1000);

});

setTimeout(() => {

rxObservable.subscribe(v => console.log(v));

}, 2000);

This code written with RxJS will exhibit the following behavior:

- Nothing for 3 seconds

- Logs

"hello world"

Let’s compare this to the behavior of streams:

import { fromNext, EOF, subscribe } from "observables-with-streams";

const owsObservable = fromNext(next => {

setTimeout(() => {

next("hello world");

next(EOF);

}, 1000);

});

setTimeout(() => {

owsObservable.pipeTo(

subscribe(v => console.log(v))),

);

}, 2000);

This ows example will do the following:

- Nothing for 2 seconds

- Logs

"hello world"

So the ows example waits one second less until it logs something. Because streams are tailored to a single consumer, streams tap their data source immediately. The data is already buffered up by the time the subscribe() call is executed. On the other hand, observables create a new source for every subscriber.

Note: Push models can be converted to a pull model and vice versa. To quote Domenic in this StackOverflow post: “To build push on top of pull, constantly be pulling from the pull API, and then push out the chunks to any consumers. To build pull on top of push, subscribe to the push API immediately, create a buffer that accumulates all results, and when someone pulls, grab it from that buffer. (Or wait until the buffer becomes non-empty, if your consumer is pulling faster than the wrapped push API is pushing.) The latter is generally much more code to write than the former.”.

Scheduling

When talking to Jake Archibald about this, he pointed out that there might also be a difference in task timing. And of course, he turned out to be right. What a jerk.

Here’s two more pieces of code that look the equivalent, but behave differently:

import { Observable } from "rxjs";

new Observable(subscriber => {

console.log("before");

subscriber.next("value");

console.log("after");

}).subscribe(value => {

console.log("received:", value);

});

Running this RxJS code, you will see the following logs:

beforereceived: valueafter

import { fromNext, subscribe } from "observables-with-streams";

fromNext(next => {

console.log("before");

next("value");

console.log("after");

}).pipeTo(

subscribe(value => {

console.log("received:", value);

})

);

With ows, you will see these logs:

beforeafterreceived: value

To put it in a sentence: RxJS observables deliver their values synchronously to subscribers. Streams run their processing steps in a microtask, making them asynchronous. While I have not found this problematic, it’s something you should be aware of! If you use streams (or ows) to handle events, you need to be mindful about task boundaries. Code that uses preventDefault(), event capturing or other APIs that require to be called within the same task, might not work as expected.

Is ows useful?

Regardless of whether ows is useful as an RP framework, it is definitely useful as a little toolkit for handling streams of all kinds. You can concatenate partial responses, employ a streaming JSON parser when hitting APIs to process the response, or just use to make sure your asynchronous event handlers finish running before processing the next event.

But is ows useful for reactive programming? I chose to answer this question through trial by fire and wrote an app. Luckily, I had an itch that I needed to scratch:

When you take a picture with your camera, the camera needs to focus on a subject. The “focus point”, the point in space that the camera is focusing on, is often shown on the screen of your camera. But not only that specific point is in focus. Subjects closer to the camera (and subjects further away) can also appear sharp on the picture that you take, depending on how much they are deviating from the focus point. The region that subjects can move around in and still remain in focus is called the “Depth of Field”, or DoF for short. Its size depends on a number of things: Focal length and aperture of the lens, subject distance and sensor size of the camera to begin with. There a number of apps out there that calculate the DoF for you based on these variables, but some have a disappointing UX or only expose a subset of the data I am interested in.

As any self-respecting web developer who technically had other, more pressing responsibilities, I procrastinated by writing my own app. The tool that came out of this effort is called DoF Tool. Another uninspired name. DoF Tool is open source and makes use of observables-with-streams for all of the UI and user interactions. The ows module is highly tree-shakable, so it should be used with a bundler. For DoF Tool I’m using Rollup. However, if you just want to take ows for a quick spin to try it out, you can include it from a CDN like JSDelivr as one big bundle:

<script src="https://cdn.jsdelivr.net/npm/observables-with-streams@latest/dist/really-big-bundle.js"></script>

<script>

const myButton = document.querySelector("...");

ows.fromEvent(myButton, "click").pipeThrough(ows.map(/* ... */));

// ...

</script>

The overall pattern I ended up with in DoF Tool is the following:

// Rollup is smart enough to tree-shake despite

// the * import.

import * as ows from "observables-with-streams";

ows

.combineLatest(

// Aperture slider

ows

.fromAsyncFunction(async () => {

const slider = memoizedQuerySelector("#aperture scroll-slider");

slider.value = (await getLastValueFromIdb("aperture")) || 2.8;

return ows.fromInput(slider);

})

.pipeThrough(ows.concatAll()),

// Focal length slider

ows

.fromAsyncFunction(async () => {

const slider = memoizedQuerySelector("#focal scroll-slider");

slider.value = (await getLastValueFromIdb("focal")) || 50;

return ows.fromInput(slider);

})

.pipeThrough(ows.concatAll())

// ... other inputs

)

.pipeThrough(ows.map(calculateFocalPlanes))

.pipeThrough(ows.map(calculateFieldOfView))

.pipeThrough(ows.forEach(adjustDOM))

// Only store changes in idb every second

.pipeThrough(ows.debounce(1000))

.pipeThrough(ows.forEach(storeValuesInIDB))

.pipeTo(ows.discard());

I create a couple of observables asynchronously so I can load the last values the user had from IndexedDB. Once they are initialized, I combine all my input data with combineLatest, map it through the function that do all the required math and finally use forEach to plug the resulting numbers back into the DOM. I also store the settings in IndexedDB, only every second or so.

I have to say: I enjoyed writing an app this way. And ows held up so well that I think the experiment is a success. I didn’t encounter any problems related to the differences outlined above. Now, I know that this is not a very complex app so this verdict might not hold up at scale. YMMV. I’d love to hear from some more experienced reactive programmers what they think.

Performance

Maybe somewhat surprisingly, I did not do any benchmarks. While I think there’s a good chance that RxJS will perform better in a benchmarking scenario, I have grown skeptical of the relevance of those kinds of benchmarks. The app performs well on a wide spectrum of devices (including the Nokia 2!), and that’s all that matters to me in the end. I was also more interested in comparing capabilities and developer experience first before jumping straight into the performance rabbit hole.

Library size & cross-browser support

The primary type used in ows is ReadableStream, which is supported in all major browsers. However, the operators are implemented as TransformStreams and sinks as WritableStreams, the support for which is more lacking. At the time of writing, only Blink-based browsers have full support for all stream types. Firefox supports neither WritableStreams, TransformStream nor the pipeTo() or pipeThrough() methods. Safari is also lacking support for WritableStream.

To run ows in these browsers, you’d need to load a polyfill, like Mattias Buelens’ excellent web-streams-polyfill, which adds a whopping 17KiB after brotli. While that is a lot, this additional weight will automatically go away when browsers catch up.

Why is that polyfill so big? As I mentioned earlier, streams are a low-level primitive with lots of capabilities under the hood. Apart from supporting backpressure, the spec also contains a subtype for each stream that allows reading/writing data straight from and to an ArrayBuffer for increased memory-efficiency. All these things have to be included in a proper polyfill.

Loading the polyfill

If you wanted to use ows (it’s just an experiment, remember?), make sure to only load the polyfill if the browser requires it. You’ll want to make sure that your app’s payload goes down if and when browsers catch up, without having to re-deploy. Here’s how I’m doing that in DoF Tool:

Note: Currently, due to some requirements in the spec, you have to use nothing from the polyfill or use all 3 types from the polyfill. You can’t mix-and-match. There is an issue for that.

import { init } from "./main.js";

(async function() {

const hasReadableStream = typeof ReadableStream !== "undefined";

const hasWritableStream = typeof WritableStream !== "undefined";

const hasTransformStream = typeof TransformStream !== "undefined";

if (!hasReadableStream || !hasWritableStream || !hasTransformStream) {

await import("web-streams-polyfill/dist/polyfill.es2018.mjs");

}

init();

})();

Note that I am statically importing my app’s main code but expose it wrapped in an init function. This way the app’s code ends up in the main bundle and the app starts way quicker when no polyfill is needed.

Conclusion

Getting my feet wet with reactive programming was really fun. If you haven’t tried it, I’d recommend you give it a spin. Use ows. Use RxJS. Use Svelte 3 or CycleJS. Use something else. It doesn’t really matter. My point is that RP makes developing UIs very enjoyable.

Is using streams for reactive programming a good idea? Probably not. The fact that the scheduling is different and could make event handling problematic makes it less viable then one of the smaller RP implementations like MostJS. That being said, it worked just fine for my app and is extremely small for browsers that support streams.

Apart from the specific RP use-case, I think that streams are an incredibly well-designed API and have become a Swiss army knife for me. I think every web developer should strive to be familiar with them. They can be useful in a variety of situations, not only to process fetch(). Sometimes, a little stream here and there can make your life a lot easier!

Thanks to Domenic, Jake and Jason for their feedback on this blog post!