Can you use the DOM in WebAssembly? Rust says yes, other people say no. Before we can resolve that dissonnance, I need to shine some light on what raw WebAssembly can do.

When you go to WebAssembly.org, the very first thing you see is that it’s a “stack-based virtual machine”.

It’s absolutely not necessary to understand what that means, or even look at the WebAssembly VM specification to make good use of WebAssembly. This is not required reading. However, it can be helpful to have a deeper understanding of this ominous VM to understand what is within the capabilities of a WebAssembly module and what certain errors mean.

Putting the “Assembly” in “WebAssembly”

While WebAssembly is famously “Neither Web, Nor Assembly”, it does share some characteristics with other assembly languages. For example: The spec contains both a specification for the binary representation as well as a human-readable text representation. This text format is called “wat” and is short for “WebAssembly text format”. You can use Wat to hand-craft WebAssembly modules. To turn a Wasm module into Wat, or to turn a Wat file back into a Wasm binary, use wasm2wat or wat2wasm from the WebAssembly Binary Toolkit.

A small WebAssembly module

I am not going to explain all the details of the WebAssembly virtual machine, but just going through list a couple of short examples here that should help you understand how to read Wat. If you want to know more details, I recommend browsing MDN or even the spec.

You can follow along on your own machine with the tools mentioned above, open the hosted version of the demos (linked under each example) or use WebAssembly.studio, which has support for Wat but also C, Rust and AssemblyScript.

(;

Filename: add.wat

This is a block comment.

;)

(module

(func $add (param $p1 i32) (param $p2 i32) (result i32)

;; Push parameter $p1 onto the stack

local.get $p1

;; Push parameter $p2 onto the stack

local.get $p2

;; Pop two values off the stack and push their sum

i32.add

;; The top of the stack is the return value

)

(export "add" (func $add))

)

The file starts with a module expression, which is a list of declarations what the module contains. This can be a multitude of things, but in this case it’s just the declaration of a function and an export statement. Everything that starts with $ is a named identifier and is turned into a unique number during compilation. These identifiers can be omitted (and the compiler will take care of the numbering), but the named identifiers make Wat code much easier to follow.

After assembling our .wat file with wat2wasm, we can disassemble it again (for lols) with wasm2wat. The result is below.

(module

(type (;0;) (func (param i32 i32) (result i32)))

(func (;0;) (type 0) (param i32 i32) (result i32)

local.get 0

local.get 1

i32.add

)

(export "add" (func 0))

)

As you can see, the named identifiers have disappeared and have been replaced with (somewhat) helpful comments by the disassembler. You can also see a type declaration that was generated for you by wat2wasm. It’s technically always necessary to declare a function’s type before declaring the function itself, but because the type is fully inferable from the declaration, wat2wasm injects the type declaration for us. Within this context, function type declarations will seem a bit redundant, but they will become more useful when we talk about function imports later.

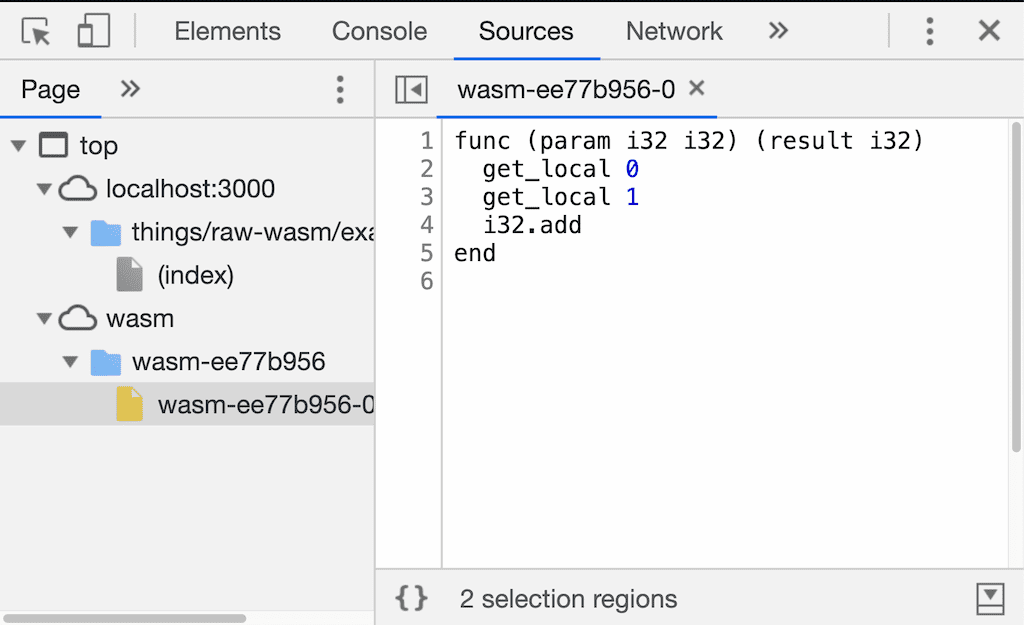

Pro tip: Did you know that the “Source” panel in DevTools will automatically disassemble .wasm files for you?

A function declaration consists of a couple of items, starting with func keyword, followed by the (optional) identifier. We also need to specify a list of parameters with their types, the return type and an optional list of local variables. The function body is itself a list of instructions for the VM’s stack. Using these instructions you can push values onto the stack, pop values off the stack and replace them with the result of an operation or load and store values in local variables, global variables or even memory (more about that later). A function must leave exactly one value on the stack as the function’s return value.

Writing code for a stack-based machine can sometimes feel a bit weird. Wat also offers “folded” instructions, which look a bit like functional programming. The following two function declarations are equivalent:

(func $add (param $p1 i32) (param $p2 i32) (result i32)

local.get $p1

local.get $p2

i32.add

)

(func $add (param $p1 i32) (param $p2 i32) (result i32)

(i32.add (local.get $p1) (local.get $p2))

)

The export declaration can assign a name to an item from the module declaration and make it available externally. In our example above we exported the $add function with the name add.

Loading a raw WebAssembly module

If we compile our add.wat file to a add.wasm file and load it in the browser (or in node, if you fancy), you should see an add() function on the exports property of your module instance.

<script>

async function run() {

const {instance} = await WebAssembly.instantiateStreaming(

fetch("./add.wasm")

);

const r = instance.exports.add(1, 2);

console.log(r);

}

run();

</script>

The compilation of a WebAssembly module can start even when the module is still downloading. The bigger the wasm module, the more important it is to parallelize downloading and compilation using instantiateStreaming. There is two pitfalls with this functions, though: Firstly, it will throw if you don’t have the right Content-Type header, so make sure you set it to application/wasm for all .wasm files. Secondly, Safari doesn’t support instantiateStreaming at all yet, so I tend to use this drop-in replacement:

<script>

async function maybeInstantiateStreaming(path, ...opts) {

// Start the download asap.

const f = fetch(path);

try {

// This will throw either if `instantiateStreaming` is

// undefined or the `Content-Type` header is wrong.

return await WebAssembly.instantiateStreaming(

f,

...opts

);

} catch(_e) {

// If it fails for any reason, fall back to downloading

// the entire module as an ArrayBuffer.

return WebAssembly.instantiate(

await f.then(f => f.arrayBuffer()),

...opts

);

}

}

</script>

This is similar to what Emscripten does and has worked well in the past.

Functions

A WebAssembly module can have multiple functions, but not all of them need to be exported:

;; Filename: contrived.wat

(module

(func $add (; …same as before… ;))

(func $add2 (param $p1 i32) (result i32)

local.get $p1

;; Push the constant 2 onto the stack

i32.const 2

;; Call our old function

call $add

)

(func $add3 (param $p1 i32) (result i32)

local.get $p1

;; Push the constant 3 onto the stack

i32.const 3

;; Call our old function

call $add

)

(export "add2" (func $add2))

(export "add3" (func $add3))

)

Notice how add2 and add3 are exported, but add is not. As such add() will not be callable from JavaScript. It’s only used in the bodies of our other functions.

WebAssembly modules can not only export functions but also expect a function to be passed to the WebAssembly module at instantiation time by specifying an import:

;; Filename: funcimport.wat

(module

;; A function with no parameters and no return value.

(type $log (func (param) (result)))

;; Expect a function called `log` on the `funcs` module

(import "funcs" "log" (func $log))

;; Our function with no parameters and no return value.

(func $doLog (param) (result)

;; Call the imported function

call $log

)

(export "doLog" (func $doLog))

)

If we load this module with our previous loader code, it will error. It is expecting a function in its imports object and we have provided none. Let’s fix that:

<script>

async function run() {

function log() {

console.log("This is the log() function");

}

const {instance} = await WebAssembly.instantiateStreaming(

fetch("./funcimport.wasm"),

{

funcs: {log}

}

)

instance.exports.doLog();

}

run();

</script>

Running this will cause a log to appear in the console. We just called a WebAssembly function from JavaScript, and then we called a JavaScript function from WebAssembly. Of course both these function calls could have passed some parameters and have return values. But when doing that it’s important to keep in mind that JavaScript only has IEEE754 64-bit floats (“double”). Some types, like 64-bit integers, cannot be passed to JavaScript without loss in precision.

Importing functions from JavaScript is a big puzzle piece on how Rust makes DOM operations possible from within Rust code with wasm-bindgen. This is of course glossing over some important and clever details and I’ll talk about those in a different blog post.

Memory

There’s only so much you can do when all you have is a stack. After all, the very definition of a stack is that you can only ever reach the value that is on top. So most WebAssembly modules export a chunk of linear memory to work on. It’s worth noting that you can also import a memory from the host environment instead of exporting it yourself. Whatever you prefer, you can only have exactly one memory unit overall (at the time of writing).

This example is a bit contrived, so bear with me. The function add2() loads the first integer from memory, adds 2 to it and stores it in the next position in memory.

;; Filename: memory.wat

(module

;; Create memory with a size of 1 page (= 64KiB)

;; that is growable to up to 100 pages.

(memory $mem 1 100)

;; Export that memory

(export "memory" (memory $mem))

;; Our function with no parameters and no return value,

;; but with a local variable for temporary storage.

(func $add2 (param) (result) (local $tmp i32)

;; Load an i32 from address 0 and put it on the stack

i32.const 0

i32.load

;; Push 2 onto the stack and add the values

i32.const 2

i32.add

;; Temporarily store the result in the parameter

local.set $tmp

;; Store that value at address 4

i32.const 4

local.get $tmp

i32.store

)

(export "add2" (func $add2))

)

Note: We could avoid the temporary store in

$p1by moving thei32.const 4to the very start of the function. Many people will see that as a simplification and most compilers will actually do that for you. But for educational purposes I chose the more imperative but longer version.

WebAssembly.Memory is just a sequence of bits for storage. You have to decide how to read or write to it. That’s why there is a separate incarnation of store and load for each WebAssembly type. In the above example we are loading signed 32-bit integers, so we are using i32.load and i32.store. This is similar to how ArrayBuffers are just a series of bits that you need to interpret by using Float32Array, Int8Array and friends.

To inspect the memory from JavaScript, we need to grab memory from our exports object. From that point on, it behaves like any ArrayBuffer.

<script>

async function run() {

const {instance} = await WebAssembly.instantiateStreaming(

fetch("./memory.wasm")

);

const mem = new Int32Array(instance.exports.memory.buffer);

mem[0] = 40;

instance.exports.add2();

console.log(mem[0], mem[1]);

}

run();

</script>

Strings? Objects?

WebAssembly can only work with numbers as parameters. It can also only return numbers. At some point you will have functions where you’d want to accept strings or maybe even JSON-like objects. What do you do? Ultimately it comes down to an agreement how to encode these more complex data types into numbers. I’ll talk more about this when we transition to more high-level programming languages.

What I left out

There are a couple of things that WebAssembly modules can do that I didn’t talk about:

- Memory initialization: Memory can be initialized with data in the WebAssembly file. Take a look at

datastringin the memory initializers and data segments. - Tables: Tables are mostly useful to implement concepts like function points and consequently patterns like dynamic dispatch or dynamic linking.

- Globals: Yes, you can have global variables.

- Many, many other operations on stack values.

- and probably other stuff 🤷♂️

AssemblyScript

Writing Wat by hand can feel a bit awkward and is probably not the most productive way to create WebAssembly modules. AssemblyScript is a language with TypeScript’s syntax compiles to WebAssembly and closely mimics the capabilities of the WebAssembly VM. The functions that are provided by the standard library often map straight to WebAssembly VM instructions. I highly recommend taking a look!

Conclusion

Is Wat useful for your daily life as a web developer? Probably not. I have found it useful in the past to be able to inspect a Wasm file to understand why something was going wrong. It also helped me understand more easily how Emscripten is able emulate a filesystem or how Rust’s wasm-bindgen is able to expose DOM APIs even though WebAssembly has no access to them (by default). As I said before: This post is not required reading for any web developer. But it can be handy to know your way around wasm2wat and Wat if you are messing around with WebAssembly.