How do I copy an object in JavaScript? It’s a simple question, without a simple answer.

Chinese translation: 中文版

Russian translation: русском

Uzbek translation: O'zbek

Call by reference

JavaScript passes everything by reference. In case you don’t know what that means, here’s an example:

function mutate(obj) {

obj.a = true;

}

const obj = {a: false};

mutate(obj)

console.log(obj.a); // prints true

The function mutate changes the object it gets passed as a parameter. In a “call by value” environment, the function would get passed the value — so a copy — that the function could work with. Any changes the function makes to the object would not be visible outside of that function. But in a “call by reference” environment like JavaScript, the function gets a — you guessed it — reference, and will mutate the actual object itself. The console.log at the end will therefore print true.

Sometimes, however, you might want to keep your original object and create a copy for other functions to work with.

Shallow copy: Object.assign()

One way to copy an object is to use Object.assign(target, sources...). It takes an arbitrary number of source objects, enumerating all of their own properties and assigning them to target. If we use a fresh, empty object as target, we are basically copying.

const obj = /* ... */;

const copy = Object.assign({}, obj);

This, however, is merely a shallow copy. If our object contains objects, they will remain shared references, which is not what we want:

function mutateDeepObject(obj) {

obj.a.thing = true;

}

const obj = {a: {thing: false}};

const copy = Object.assign({}, obj);

mutateDeepObject(copy)

console.log(obj.a.thing); // prints true

Another thing to potentially trip over is that Object.assign() turns getters into simple properties.

So what now? Turns out, there is a couple of ways to create a deep copy of an object.

Note: Some people have asked about the object spread operator. Object spread will also create a shallow copy.

JSON.parse

One of the oldest way to create copies of an object is to turn the object into its JSON string representation and then parse it back to an object. It feels a bit heavy-handed, but it does work:

const obj = /* ... */;

const copy = JSON.parse(JSON.stringify(obj));

The downside here is that you create a temporary, potentially big string just to pipe it back into a parser. Another downside is that this approach cannot deal with cyclic objects. And despite what you might think, those can happen quite easily. For example when you are building tree-like data structures where a node references its parent, and the parent in turn references its own children.

const x = {};

const y = {x};

x.y = y; // Cycle: x.y.x.y.x.y.x.y.x...

const copy = JSON.parse(JSON.stringify(x)); // throws!

Additionally, things like Maps, Sets, RegExps, Dates, ArrayBuffers and other built-in types just get lost at serialization.

Structured Clone

Structured cloning is an existing algorithm that is used to transfer values from one realm into another. For example, this is used whenever you call postMessage to send a message to another window or a WebWorker. The nice thing about structured cloning is that it handles cyclic objects and supports a wide set of built-in types. The problem is that at the time of writing the algorithm is not exposed directly, only as a part of other APIs. I guess we’ll have to look at those then, won‘t we…

MessageChannel

As I said, whenever you call postMessage the structured clone algorithm is used. We can create a MessageChannel and send ourselves a message. On the receiving end the message contains a structural clone of our original data object.

function structuralClone(obj) {

return new Promise(resolve => {

const {port1, port2} = new MessageChannel();

port2.onmessage = ev => resolve(ev.data);

port1.postMessage(obj);

});

}

const obj = /* ... */;

const clone = await structuralClone(obj);

The downside of this approach is that it is asynchronous. That is not a big deal, but sometimes you need a synchronous way of deep-copying an object.

History API

If you’ve ever used history.pushState() to build an SPA you know that you can provide a state object to save alongside the URL. It turns out that this state object is structurally cloned — synchronously. We have to be careful not to mess with any program logic that might use the state object, so we need to restore the original state after we’re done cloning. To prevent any events from firing, use history.replaceState() instead of history.pushState().

function structuralClone(obj) {

const oldState = history.state;

history.replaceState(obj, document.title);

const copy = history.state;

history.replaceState(oldState, document.title);

return copy;

}

const obj = /* ... */;

const clone = structuralClone(obj);

Once again, it feels a bit heavy-handed to tap into the browser’s engine just to copy an object, but you gotta do what’cha gotta do. Also, Safari limits the amount of calls to replaceState to 100 within a 30 second window.

Notification API

After tweet-storming about this whole journey on Twitter, Jeremy Banks showed me that there’s a 3rd way to tap into structural cloning: The Notification API. Notifications have a data object associated with them that gets cloned.

function structuralClone(obj) {

return new Notification('', {data: obj, silent: true}).data;

}

const obj = /* ... */;

const clone = structuralClone(obj);

Short, concise. I liked it! However, it basically kicks of the permission machinery within the browser, so I suspected it to be quite slow. Safari, for some reason, always returns undefined for the data object.

Performance extravaganza

I wanted to measure which of these ways is the most performant. In my first (naïve) attempt, I took a small JSON object and piped it through these different ways of cloning an object a thousand times. Luckily, Mathias Bynens told me that V8 has a cache for when you add properties to an object. I was benchmarking the cache more than anything else. To ensure I never hit the cache, I wrote a function that generates objects of given depth and width using random key names and re-ran the test.

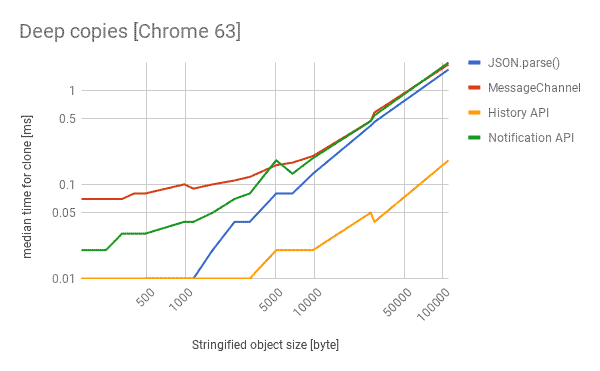

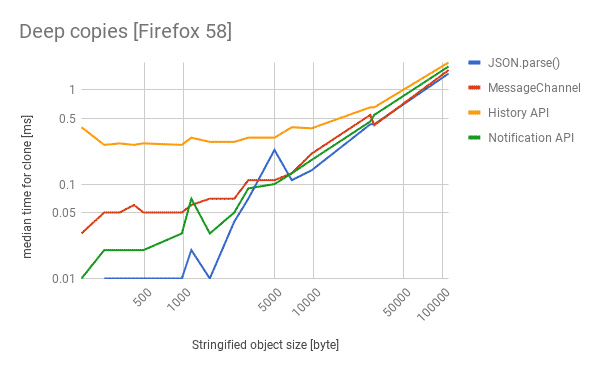

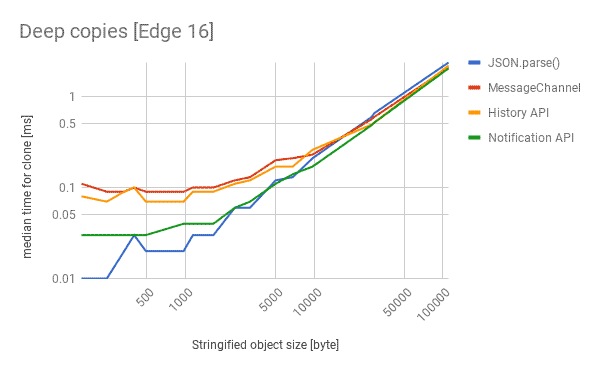

Graphs!

Here’s how the different techniques perform in Chrome, Firefox and Edge. Lower is better.

Conclusion

So what do we take away from this?

- If you don’t expect cyclic objects and don’t need to preserve built-in types, you get the fastest clone across all browsers by using

JSON.parse(JSON.stringify()), which I found quite surprising. - If you want a proper structured clone,

MessageChannelis your only reliable cross-browser choice.

Wouldn’t it be better if we just had structuredClone() as a function on the platform? I certainly think so and revived an old issue on the HTML spec to reconsider this approach.